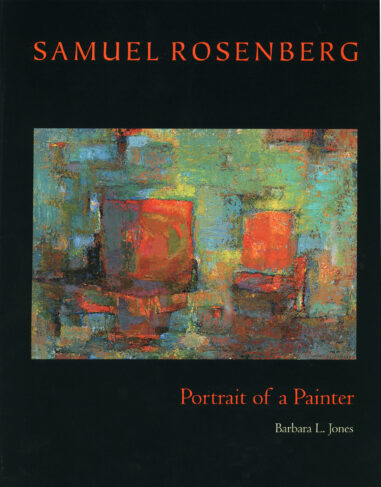

Samuel Rosenberg

Portrait Of A Painter

A solidly satisfying study of one artist's place in the history of American art.

Request Exam or Desk Copy. Request Review Copy

While other artists moved to New York or Paris, painter Samuel Rosenberg (1896-1972) never left the city he called home. From the age of twelve, when he took his first art class at a settlement house in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, through a vigorous career that spanned six decades, Rosenberg was challenged by the complex city whose artistic legacy he did much to shape. In Pittsburgh, Rosenberg created more than five hundred paintings, engaged with the dynamic progress of American painting in the twentieth century, and inspired generations of students. This book is the first full study of his work and influence.

The constancyof Rosenberg’s career was change. He began as a portraitist (1915-1930), influenced by Velazquez, Rembrandt, Matisse, and later, Picasso. In the 1930s, however, Rosenberg turned to portray the city around him. Inspired by the steep hills, densely polluted atmosphere, crooked houses, and layered immigrant populations with intersecting poverties, he created emotional urban landscapes that ensured Pittsburgh’s place in the American regionalist art movement.Rosenberg’s focus was the Hill District, where he lived as a young man. In poignant, socially conscious paintings, he traced the transitions of this gritty, multiethnic neighborhood through the Great Depression and Pittsburgh’s early experiments in urban renewal. “Yes, I know there are artists in town who sneer at Pittsburgh, who want to go to Venice and paint canals,” Rosenberg told a reporter. “But the artist who dislikes the town should . . . stay here and put his hate into pictures of the Pittsburgh scene. In doing so, he would have something to say.”In the 1940s, responding to the horrors of World War II, Rosenberg’s subjects became more universal and allegorical. In paintings such as Israel (1945), his most reproduced work, haunting human figures do not allow viewers to remain indifferent to the world situation. Here he began experiments with abstraction and the quality of light, a search he would continue for the rest of his life.From 1949 until his death in 1972, Rosenberg developed his own form of abstract expressionism, translating emotion with color, but without entirely abandoning representation. Using sequential layers of translucent color and transparent glazes, Rosenberg was able to achieve a penetrating, shimmering effect in his work. His paintings from this period are reminiscent of stained glass windows in that they seem to emit light rather than reflect it.Samuel Rosenberg’s paintings were exhibited widely, from the World’s Fair (1939) to the nation’s preeminent museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. He had twenty-six solo exhibitions during his lifetime, and he was accepted into the prestigious Carnegie International in 1920, 1925, and every subsequent exhibition from 1933 to 1967.But it is possible that Rosenberg’s most enduring legacy is his teaching. For more than forty years he taught drawing and painting at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), where his students included Philip Pearlstein, Mel Bochner, and Andy Warhol-whom Rosenberg saved from expulsion in 1947. He chaired the art department at the Pennsylvania College for Women (now Chatham College). He directed art programs and taught for decades at two community art schools: the Irene Kaufmann Settlement in the Hill District and the Isaac Seder Educational Center for the Young Men’s and Women’s Hebrew Association, which merged in 1961. A revered and devoted master teacher, he awakened several generations of Pittsburgh artists to the “adventure,” as he called it, of art.Samuel Rosenberg: Portrait of a Painter accompanies the first major retrospective of his work since 1960. In a thorough and carefully researched essay, accompanying eighty-two color and fifty black-and-white reproductions, curator Barbara L. Jones tells the story of Rosenberg’s life, his evolving artistic vision, and his teaching legacy. She also provides biographical, exhibition, and award chronologies, along with a complete catalog of paintings and preparatory sketches. Lively sidebars by regional historians Barbara Burstin, Eric Davin, and Laurence Glasco, and by artist and former student Bennard Perlman, give social and cultural context, recreating the Pittsburgh in which this remarkable artist lived and worked.

More Praise

I have long been impressed with the remarkable diversity of Sam Rosenberg's art—from moving scenes of depression-era Pittsburgh to brilliant painterly abstractions. Barbara Jones's book explores Rosenberg's life, providing us with the cultural and historical background necessary to understand his work as an artist and a teacher.

Jones is to be applauded for her extraordinary, exhaustively researched, organized, lucid, and comprehensive book. Greatly needed. Highly recommended.

Provides an interesting picture and wonderful insight into Pittsburgh, set against the career of one of the region's most important artists.

248 Pages, 8.5 x 10.5 in.

July, 2003

isbn : 9780822942139

about the author

Barbara L. Jones is curator of the Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg, Pennsylvania.

learn more