Five Questions for Joseph Cialdella, author of Motor City Green

Five Questions for Joseph Cialdella, author of Motor City Green

Q: What drew you to this topic/subject area?

A: I was born and raised in Kalamazoo, MI, which is on the west side of the state, and we didn’t spend much time in Detroit, which is on the east side of the state. That changed when I went to college [at the University of Michigan’s Residential College], and was fortunate to participate in several engaged learning courses where we had the opportunity to learn about the city and work with organizations and communities in Detroit.

I was especially moved by the work being done around urban gardening by long-time residents, many of whom were African Americans. I was struck by the way these vibrant green spaces contrasted with spaces that were vacant of their former uses. Gardens contributed to resident’s sense of place and worked against the misperception that Detroit is an abandoned city.

I carried this interest to graduate school, but as a historically-minded student, I was also curious about the gardens, green spaces, and gardeners that came before. As someone with a humanities lens, I was drawn to the topic because it seemed to be a way to better understand the changing reasons why people and communities create gardens and the meanings they give to nature and green spaces in urban and industrial places over time.

Given Detroit’s history of racial division, I was also drawn to the topic because it was a way to more closely examine the assumptions about race, class, and the environment that are often not explicit when we think about gardens and green spaces. I wanted to learn how a piece of Detroit’s environmental past could help us better understand urban gardening and farming as a part of a longer trajectory that led to the city’s cultural landscape as we know it today.

Q: Do you have your own garden? How big is it and what do you like to grow?

A: Unfortunately, and perhaps ironically, I don’t actually have much space for a garden at the moment! But this means I get to enjoy and use places like public parks, gardens, famer’s markets, and outdoor spaces even more than I might otherwise.

We’re fortunate to have these types of places, and not having a garden at home often makes me remember how important they are for one’s well-being. I’ve also helped my mom garden and landscape since I was a kid, and continue to do so today.

In my mom’s garden, we had a section for vegetables like tomatoes, cucumbers, eggplant, squash, green beans, and herbs. Where I live now, we’ve tried to create a garden using containers on the porch and patio for vegetables like tomatoes, peppers, and a variety of herbs for cooking. I like sunflowers, but the chipmunks usually get to them before they can reach their full potential. Zinnias have been great for borders along sidewalks.

Q: How can the information in your book be applied to areas outside Detroit?

A: Urban greening can often seem like a new endeavor because there’s so much necessary urgency and excitement around it today. But most of the information in Motor City Green is historical, presenting a story about Detroit’s past. I think this historical mindset can also be applied to other areas. It’s important to strive toward better knowing what happened in the past, so that our present and future endeavors can aim to learn from what came before.

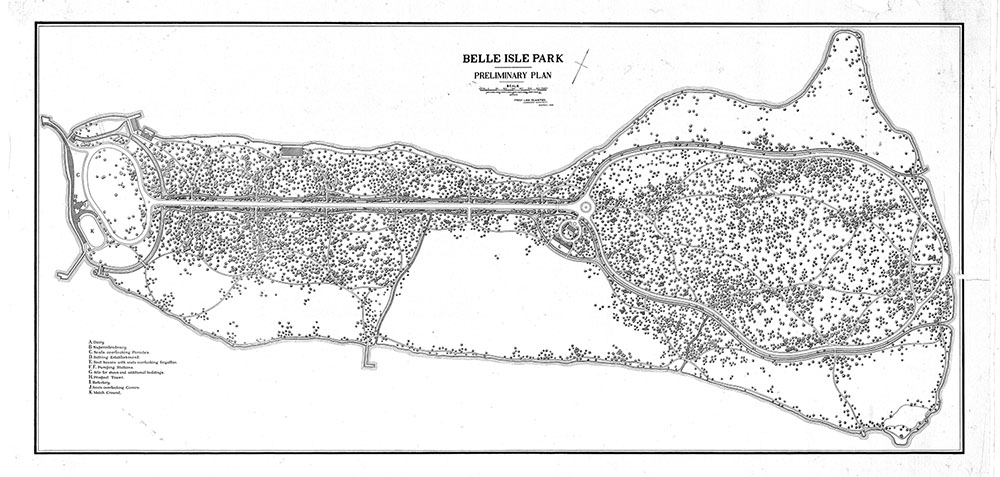

For example, cultural beliefs about the value of green space sometimes meant that certain groups of people, such as African Americans, were excluded from public parks and urban green spaces, and thus had to create their own, separate but unequal access and connections to nature in the city. Polish immigrants and working class residents disproportionately had to grow their own food on vacant lots out of dire necessity.

Parks and gardens are not neutral spaces. They are heavily influenced by our social structures, cultural beliefs, and the inequities these create. I think that’s important information for people to know as they think about the meaning of parks, gardens, and green spaces in other areas and how we might better sustain them socially and environmentally.

Part of the reason I chose to research and write about Detroit is that more has been written about parks and green spaces in other cities. That said, I think the broader story in Motor City Green—one about the tensions and opportunities taken up by diverse people and organizations in urban areas as they advocated for and used green spaces like gardens alongside industry—is useful for anyone interested in learning about the fascinating ways green spaces like gardens shape the social and cultural meaning of urban areas.

Q: Do you have any advice for someone who might want to start a community garden or farm?

A: There’s a lot of interest in community gardening and urban farming today. So my advice for someone who might want to start a community garden or farm would be to look carefully at who is already doing this work in your area, and seek out ways to build positive relationships with them and work together toward shared goals and mutual benefit.

There are technical aspects, like getting the soil tested, but I think understanding the social and cultural context in which you are looking to create a garden, farm, or other green space is just as important as knowing how to grow the plants. Anyone looking to start a community garden or farm needs to make sure there’s a community there that wants a garden and can support it.

Otherwise you end up with more of a personal or private garden than a community-supported one. Important questions to ask might include: Is there a need for this garden or farm? And if so, why does this need exist? Who is the community or audience for this space? Do I have support from them to create it? Who else is already doing this work? And am I the right person to be doing it?

Looking for ways to respectfully connect with and amplify work already happening, rather than starting from scratch, might be a more sustainable way to ensure community gardens and farms have a lasting place in our urban landscapes and are valued as common goods by the public and communities.

Q: What are you reading or watching right now related to your subject area?

A: Working in the public humanities, I have a different viewpoint and don’t have as many opportunities to immerse myself in my research-subject area quite as much as I once did. Events like the Flint Water Crisis put scholarship about the Great Lakes region, and the topic of water more front and center for me personally.

More connected to my specific area, I’m excited about Community of Gardens, an initiative at Smithsonian Gardens that is trying to better collect and document stories of gardening and community gardening from around the United States.

And on a completely different topic, the book I’m currently reading is Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, a collection of essays that reflects on the lessons to be found for sustaining life by cultivating deeper ways of knowing the many living things around us through indigenous stories and perspectives.

COMMENTS