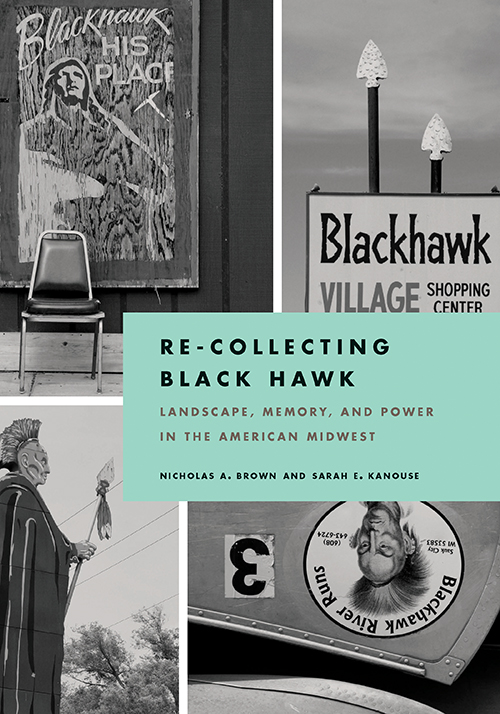

Re-Collecting Black Hawk: Q & A with Nicholas A. Brown and Sarah E. Kanouse

Re-Collecting Black Hawk: Q & A with Nicholas A. Brown and Sarah E. Kanouse

UPP welcomes Nicholas A. Brown and Sarah E. Kanouse, authors of the forthcoming Re-Collecting Black Hawk: Landscape, Memory, and Power in the American Midwest as the first of our authors to be featured in a Q&A.

UPP welcomes Nicholas A. Brown and Sarah E. Kanouse, authors of the forthcoming Re-Collecting Black Hawk: Landscape, Memory, and Power in the American Midwest as the first of our authors to be featured in a Q&A.

UPP: What was your inspiration for Re-Collecting Black Hawk?

NB: There’s no one moment that inspired the project; rather it was an organic outgrowth of our artistic and scholarly interests and quirks of personal history that all came together at the right time. I actually grew up in Madison, Wisconsin, surrounded by references to Black Hawk. As a kid I walked to Blackhawk Country Club every Fourth of July to watch the fireworks. I delivered newspapers in the Indian Hills neighborhood, raced my bike down the steep hill on Old Sauk Road, walked my dog at Indian Lake Park, and went to summer camp at Black Hawk Middle School. I also spent a lot of time camping and canoeing in southwestern Wisconsin near the site of the Bad Axe Massacre. At the time these were just names, without historical referents, but they saturated the mental maps of my childhood. And in so doing I think they subtly shaped my own assumptions and expectations about Native Americans. This personal connection wasn’t an inspiration for the project but it certainly became a compelling aspect of it.

As the familiar landscape of my childhood became increasingly unfamiliar, I gained a deeper and more intimate appreciation for concepts such as Renato Rosaldo’s “imperialist nostalgia,” which I had previously understood in more abstract terms. In the process of developing this project it also became clear how seemingly benign naming practices function as part of a larger ideological project that denies complicity and produces innocence while mourning the “loss” of indigenous presence. By naturalizing these social processes and practices, landscapes, like the one I inhabited as a kid, perpetuate the myth of the vanishing Indian and frame it as a sad but inevitable chapter in our collective history.

SK: I don’t have the same childhood connection with the Midwest – I’m originally from Los Angeles. However, I moved to Illinois in the late 1990s during a surge of activism opposing Chief Illiniwek, the “Indian” mascot of the University of Illinois. At the time relatively few non-Native people had every stopped to consider that such mascots might be offensive, but the vitriol hurled against the Native activists and their allies revealed a strangely personal, possessive investment in such acts of appropriation. Though I wasn’t centrally involved in the anti-Chief movement, being in that environment helped me better understand the relationship between struggles over representation and the material conditions of people’s lives. It also meant that the kitschy “Indian” motels and convenience stores that dotted the quaint Midwest where I found myself didn’t seem so innocent anymore.

NB: Sarah and I were living in southern Illinois—near Shawnee National Forest and a segment of the Trail of Tears—when we initially conceived of the Black Hawk project. At the time we were wrapping up another project that focused on the relationship between the Trail of Tears as a historical event and its contemporary interpretation through the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, particularly the Auto Tour Route through southern Illinois. Inspired in part by a question Philip Deloria posed in his book Indians in Unexpected Places (“How might one think about uncertainties conjured up when the non-Indian world turns to imagine a Cherokee in a Cherokee—or a Geronimo in a Cadillac?), we produced a short film called Jeep/Cherokee/Indian in order to challenge assumptions about mobility, modernity, and the continuity between past and present. Using the journal of Reverend Daniel S. Butrick, who accompanied the Cherokee on their forced removal, we retraced the route of the Trail of Tears through southern Illinois. Starting at the Ohio River on December 15 and concluding at the Mississippi River on January 26—the anniversaries of the Cherokee passage through Illinois—we set up our camera on the shoulder of the highway, near encampments listed in Butrick’s journal, and recorded the passing cars and trucks. The film, which you can still watch online, features all the Jeep Cherokees that we observed driving along the Trail of Tears. In many ways Re-Collecting Black Hawk is an outgrowth of earlier projects such as Jeep/Cherokee/Indian.

SK: When we started collaborating on the Trail of Tears piece, both of us had been working on creative projects for a few years that dealt with landscape, memory, and power in the Midwest. We were both interested in how dominant historical narratives subtend many casual, daily practices in ways that enable Americans’ legendary cultural amnesia. What does it mean to drive your Jeep Grand Cherokee on your daily commute along the Trail of Tears, for instance? Such a commute normalizes both the dispossession from the land and from the name such that it can be Anglicized and then transformed into a successful brand by an automobile company with military roots. That such practices operate beneath the level of conscious awareness is precisely the source of their ideological power and why these casual acts of appropriation are more effective “monuments” to the quietus of settler possession than the small, spatially discrete historical markers that more explicitly address these histories.

UPP: Please define for us the “image-text” style/format and explain why it works so well for this book.

“I am suspicious of images for seductively concealing more than revealing. A picture may be worth a thousand words, but none of them has any special purchase on truth.”

SK: As an artist, I am suspicious of images for seductively concealing more than revealing. A picture may be worth a thousand words, but none of them has any special purchase on truth. The interpretation of visual materials is necessarily intertextual—other images, facts, and narratives influence, explicitly or implicitly, how we ‘read’ a picture. When we look at any image, we are looking at the artist’s conscious or unconscious distillation of a matrix of representational practices. Image-makers draw upon that matrix in our own acts of representation. The image-text format we use in this book makes the inherent intertextuality of photographic production and interpretation explicit. It also, and more importantly for our purposes, actively curates it. The image-text pairings, and the progression from one image-text to another, creates a web of relationships in which both the images and the texts can take on meanings that neither could have had independently.

NB: Re-Collecting Black Hawk asks a lot of its readers. For those unfamiliar with the project it should become clear pretty quickly that the texts do not explain the images—they are not captions—nor do the images illustrate the texts. Instead the image/text pairings suggest relationships and hint at possible connections. The goal is to make the familiar productively unfamiliar and also to invite readers to re-imagine everyday landscapes. The image/text format is useful for deconstructing or unsettling landscapes conditioned by settler colonialism and also for building something new based on the recognition of continuous indigenous presence and enduring and evolving relationships with the land. The project is fundamentally about imagination and possibility. So in addition to asking a lot of readers we hope the book offers a lot too.

SK: Although the photographs document both Black Hawk’s appropriation and official commemorative sites of the Black Hawk conflict, the book is not really a documentary project. Rather, it is an extended visual essay. The word “essay” comes from the French “essai,” meaning an attempt or a trial. If documentary is a practice of making evident something existing in the world, the essay grapples explicitly with how to make sense of it. Conventional documentaries have been criticized for doing too much interpretive work for the viewer, for engendering a passivity in the spectator that undermines even the most activist goals of a producer. Essays are typically more fragmentary and more subjective than conventional documentary projects and demand more of the reader or viewer than consumption. In the book, the precise relationship between a paired image and text might be unclear, or perhaps explicit but contradictory. The book asks the reader to make their own connections as they move through the material. It functions as an open-ended invitation to “re-collect,” to re-assemble and re-associate both the visible evidence of Black Hawk’s legacy and the text fragments that point to Native presence and the politics of memory.

UPP: Your book features over 160 images. What are some of your favorites?

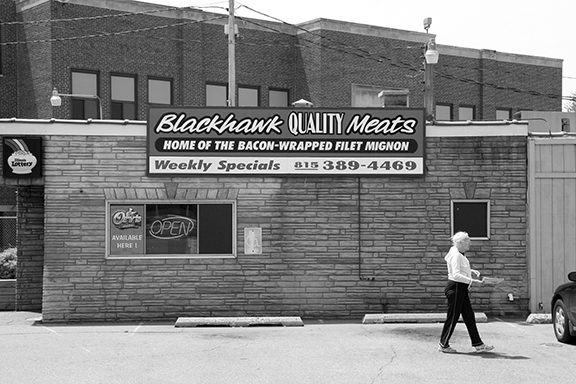

NB: This is a tough question. I like different images for different reasons. I associate certain images—Black Hawk Motel in Wisconsin Dells (pages 92-93) and Blackhawk River Runs in Mazomanie (pages 96-97) for example—with stories about our own experience photographing in the field. Other images are compelling mostly for aesthetic reasons. In some cases the particular appropriation of Black Hawk’s name is ironic or just peculiar, such as Blackhawk Bowhunters Archery Club (page 115), Blackhawk Curling Club (page 133), and Blackhawk Quality Meats (page 152). A photograph of streets signs at the intersection of W. Empire Street and S. Blackhawk Avenue in Freeport, Illinois (page 167) tells the story of the Black Hawk War as well as any text.

Other favorites include images of Blackhawk Home Sales (pages 94-95), a small business (now defunct) in Baraboo, Wisconsin that sold mobile homes. Located at a busy intersection, the modest offices are surrounded by large signs reading “You be the Judge.” There are also a couple images that include electronic message signs, and the messages that happened to display in the split-second our camera’s shutter opened resonate with our project in interesting ways. For instance, Blackhawk Lock & Safe’s sign (page 40) displayed the message: “Locked Up,” and Blackhawk Technical College’s sign (page 128) urged passers-by to “Plan Ahead.”

SK: Nick tends to like images that hold potentially ironic meanings that reinforce the book’s general approach. I am also attracted to some of the more minimal images that play up the flat surfaces of the utilitarian or pre-fab architecture that so many of these rural businesses use. Examples include images like the “Blackhawk Tennis Club” (page 51) or “Blackhawk Schools” (page 139) or “Blackhawk Center” (page 184), which have a strong graphic quality and play up the intensity of summer skies in the Midwest. Other images are metaphorically poignant, such as “Blackhawk, His Place” (page 187), which shows a weather-beaten sign featuring the outline of the local Black Hawk statue and what looks like a pickaxe. A single, empty chair sits in front of the sign, seemingly inviting Black Hawk to return but also speaking to his absence.

NB: I think my favorite images are the ones where the literal meaning, which often seems quite obvious and even mundane, is transformed within the context of the book. For example, a photograph from the campground at Black Hawk State Park in Lakeview, Iowa (page 25) depicts a row of trashcans beneath a small sign that reads “Help Black Hawk Recycle.” We paired this particular image with a short text in which the journalist Mary Annette Pember reflects critically on white guilt and the persistent desire to “help the Indians.” Within the context of the book as a whole and in relation to Pember’s text specifically, the image takes on entirely new meanings, referring to much more than just environmentally responsible ways of handling glass, plastic, and metal. As we note in our introductory essay, “Putting aside for a moment its more obvious meaning, the sign can also be read as an invitation—to campers, fishermen, birdwatchers, or anyone else who happens upon his eponymous park—to help Black Hawk re-collect, re-assemble, and re-associate his name, image, and legacy.”

UPP: You’ve said that Re-Collecting Black Hawk is a call to “practice landscape differently.” Can you expand on this?

SK: In the book, we use a quote by Mark Dorrian and Gillian Rose that quite eloquently describes how landscape is a practice. They remind us that landscapes’ meanings are neither fixed nor inherent but are instead “made to speak, invited to show themselves.” In the ordinary commemorative landscapes of the Midwest, certain narratives have been made to speak, and not others. These are largely consistent with narratives of Indian removal and pacification such that the invocation of Black Hawk serves paradoxically more to shore up settler possession of the land than question the politics of its acquisition. One way of practicing landscape differently is to change what the landscape is allowed to say, to expand the narratives that it might suggest.

NB: Practicing landscape means actively participating in its ongoing construction—understanding it as a verb rather than a noun. And practicing landscape differently, in this case, means reckoning in substantive ways with past and present forms of colonization and decolonization. It means foregrounding questions about justice as we build and inhabit alternative worlds. Dorrian and Rose remind us that histories and possible futures all cohere in present-day landscapes. “Landscapes are always perceived in a particular way at a particular time. They are mobilized, and in that mobilization may become productive: productive in relation to a past or to a future, but that relation is always drawn with regard to a present.” Re-Collecting Black Hawk is itself a mobilization (albeit modest) of Midwestern landscapes, but, more importantly, it is an invitation for others to participate in this necessary project in order to produce more just and sustainable landscapes.

More about Sarah E. Kanouse

website | facebook

More about Nicholas A. Brown

facebook

COMMENTS