Q&A with Horsepower author Joy Priest

Q&A with Horsepower author Joy Priest

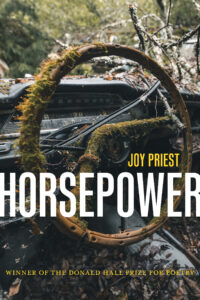

Joy Priest is the author of Horsepower, winner of the 2019 Donald Hall Prize for Poetry. Her work has appeared in ESPN, Gulf Coast, Mississippi Review, The Rumpus, Virginia Quarterly Review, and Best New Poets 2014, 2016, and 2019, among others. She is the recipient of support from the Fine Arts Work Center, The Frost Place, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the Hurston/Wright Foundation. Priest has facilitated poetry workshops with incarcerated juvenile and adult women, and has taught writing, comedy, and African American Arts & Culture at the university level. She received her MFA in poetry with a certificate in Women & Gender Studies from the University of South Carolina.

Much of your debut collection, Horsepower, explores the Louisville of the Black narrator’s youth and growing up in the urban South. As a Black Louisvillian poet, what significance does place have in this collection and in your poetics?

I was recently blessed to get a phenomenal review for Horsepower by the poet Alison Pitinii Davis on The Bind. I was really just in awe with how she understood the centrality of place and location in my curation of the collection. I think her background as a working-class poet contributed to this insightful reading. In the review, she creates for my collection a literary map after Detroit professor and scholar Frank D. Rashid, and quotes him saying, “The poets and storytellers who have written about Detroit understand that something important has happened here, and they share an impulse to reveal it. It’s difficult to live in this city, to care about it, without feeling the need to capture the experience, to define it properly, to let the outside world know about what has happened here.” And that sums up the significance of place for me as I desperately sought to reveal the contradictions within my city in some of these early poems I began writing as a younger poet around 2011.

While poems, themselves, are a kind of archive, I also always cite certain facts I’ve heard or read in reports, such as Louisville Magazine’s and the Louisville Urban League’s fairly regular reports on the West end, or the Frontline special on incarceration in Louisville, etc. One of the things I cite most often is the statistic that Louisville is the most segregated city in the country after Detroit, Milwaukee, and Cleveland. Notice, though, that Louisville is the only Southern city on this list, and, as such I think, does not get the same attention in the national conversation. So, it is a really complex society to capture and, one that—in my lifetime—doesn’t feel properly excavated or elucidated. Myself, and my teachers as I wrote these poems, quickly recognized this feeling that “something important has happened here” and my impulse to reveal it.

Tell us a little bit about the Affrilachian Poets group, as they play an important role in this collection.

So, speaking of some of these early poems that I started as a young poet and speaking of my teachers . . . the earliest poems in this collection I started around 2010/2011, about a decade ago, during undergrad. For college, I moved 70 miles down the road from Louisville—but still within the Bluegrass region/horse country—to Lexington, KY to attend the University of Kentucky. I actually ended up living in an apartment next to the Keeneland horseracing track, which I was later evicted from when my FAFSA money came in two months late one semester.

While in college, I eventually figured out I wanted to dedicate my life, seriously, to being a writer. Initially, though, I was a journalism major moonlighting as a poet. How did I become a poet moonlighting as a journalist? In 2011, while I was the features editor for the school newspaper, working at the city daily, and serving as the president of the UK chapter of the National Association of Black Journalists, the poet Frank X. Walker was one of my advisors, having been a journalism major at UK himself back in the day. Also, that year, another Black poet and professor at UK, Nikky Finney, was nominated for the National Book Award. I told Frank one day “I write poems too” (I had been writing them all my life) and gave him a folder of poems, and then one night that November I broke the wire on Nikky Finney’s National Book Award win and iconic acceptance speech. Frank came back with my poems and said, “You have the important thing, which is that you have something to say, but you need some craft classes.” Lol.

That next semester I enrolled in both Frank and Nikky’s creative writing courses. It turned out that Frank was the neologist behind the word and doctrine of “Affrilachia,” and he and Nikky were founding members of this writing collective, which seeks to make an intervention into the persistent stereotype of Appalachia as a racially homogenized region (theaffrilachianpoets.com) and elucidate the lives and living of people of color there. I started writing with them and became a member of the Affrilachian Poets in 2013 along with Jerriod Avant, Danni Quintos, and Dorian Hairston. Them’s my folks!

Shane McCrae, who blurbed the book, wrote, “Horsepower tells what it is to be a bridge in one’s family between racism and a love forged in defiance of racism; it tells what it is to need to both escape that role and embrace it.” Can you talk about this collection as an “escape narrative”?

In grad school—for my MFA, which was a lit-/theory-intensive program at the University of South Carolina, where we took seminars with the PhD students—I was very struck by the theories of “fugitivity” I came across from Black Studies scholars: Kara Keeling, Saidiya Hartman, Christina Sharpe, Fred Moten, Tina Campt, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and others. I began to understand “fugitivity” as the way Blackness was constructed in the legal codes of the United States, that to be Black is to be, inherently, fugitive from the cultural formations of Western colonialism and the governing ideology of the U.S.—that is a white supremacist, capitalist, hetero-patriarchy and all of its institutions, what Moten calls the “durational field” of slavery and its aftermaths, what Sharpe calls “the Wake,” a symptom of which we see erupting as these routine, extrajudicial killings of Black people.

In grad school—for my MFA, which was a lit-/theory-intensive program at the University of South Carolina, where we took seminars with the PhD students—I was very struck by the theories of “fugitivity” I came across from Black Studies scholars: Kara Keeling, Saidiya Hartman, Christina Sharpe, Fred Moten, Tina Campt, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and others. I began to understand “fugitivity” as the way Blackness was constructed in the legal codes of the United States, that to be Black is to be, inherently, fugitive from the cultural formations of Western colonialism and the governing ideology of the U.S.—that is a white supremacist, capitalist, hetero-patriarchy and all of its institutions, what Moten calls the “durational field” of slavery and its aftermaths, what Sharpe calls “the Wake,” a symptom of which we see erupting as these routine, extrajudicial killings of Black people.

The speaker in the collection is a Black child with a white parent. I prefer this description to “mixed-race” because I believe the latter naming erases her Blackness and erases the resulting anti-Blackness and violence she experiences even from her own white relatives, her own white mother. And because she will never be “white.” Nor does she wish to be. I wanted to present this waywardness and fugitivity as aspirational. Because we are in the same moment of slavery, in its durational field, because there has been no rupture (read: revolution) in this society and its historical constructions, because this isn’t a “post-racial society”—that hackneyed phrase people wore out upon and after the election of Obama—the speaker is Black in this country and, as such, fugitive from the household of her childhood. The speaker is a Black girl in flight. Her horses, the mechanics of fugitive-making that run through her mind. The ultimate act of escape is escaping this household and the deeply-embedded white supremacist ideology that white families pass down—overtly and subconsciously—to their children, and into which this society necessarily conscripts us.

The city of Louisville recently passed “Breonna’s Law,” banning no-knock warrants, as a result of the tragic death of 26-year-old Breonna Taylor. Yet no Louisville police officers have been arrested for her murder. What kind of progress, or lack of progress, do you see happening in Louisville in real time? What does the loss of Breonna Taylor mean to you as a Louisville resident and a poet? How can poets respond when someone in their community is killed because of police brutality or racism?

I’m suspicious of the word “progress” because I think it suggests reform along a continuum, and I’m not a proponent of reform, I’m for rupture and revolution. The hegemony repurposes reform and reproduces it as the status quo. But Louisville hasn’t even reached a level of reform yet. Louisville is just now progressing toward gentrification (with the exception of East Louisville and the downtown district, whose previous populations have already been displaced). Historically Black Louisville (the West end) hasn’t even caught up to the rest of the country and its contemporary stage of gentrification yet. However, it is in progress.

Let me give you an example: a recent Louisville Magazine article reports that “$870 million in investment is currently being planned for west Louisville,” mostly in the Russell neighborhood, which “is an appealing spot because it’s the last area to touch downtown and as of yet not experience a rush of development.” In this neighborhood, where my and Muhammad Ali’s historically-Black high school sits, “60 percent of the population lives in poverty, including about 3,000 children,” and “as a result of investment, the risk for displacement in Russell—a neighborhood of 10,000 that’s 90 percent African-American—is high.” Josh Poe, an urban planner and local organizer who independently authored, “Redlining Louisville: The History of Race, Class, and Real Estate,” says “There’s no neighborhood in the country that I can find that’s receiving the amount of investment that Russell is getting.” “Progress,” as conducted by the ruling elite, can mean social and literal death for Black people. So I ask: whose progress?

The loss of Breonna Taylor is situated in that emotional context, for me, of the social and literal death of Black Louisvillians. Though she was not living in West Louisville at the time of her murder by Louisville police, the affidavits show that police obtained the no-knock warrant because her car was spotted at the house of the main suspect of the warrant, which was in West Louisville. Breonna’s murder to me demonstrates that even though she had momentarily and geographically escaped—either literally (I don’t know where she grew up) or figuratively—the police state and surveillance that disenfranchised West Louisvillians live under, she could not escape what the poet June Jordan called the “ghettoization of the mind,” the ghetto that exists in the imagination of Louisville’s ruling elite and its state apparatus, in which, for them, all Black people reside.

Aside from intellectualizing this, I am heartbroken, of course, and enraged, more and more, each day as Mayor Greg Fischer and our first Black AG Daniel Cameron (a mentee of Mitch McConnell) stall and grandstand to distract us from our demands, and, as a writer, I intend to give them hell. I suppose I see progress, right now, in Rep. Charles Booker’s coalition politics in his campaign to take Mitch McConnell’s senate seat, and the unusual support for a candidate like him across Kentucky. He lives in the West end and he’s been out in the streets with those protesting Breonna Taylor’s murder, but he also has pledged himself as a representative of working-class whites in Kentucky, and I think he has movement potential leading up to November. I think he could unseat McConnell after 35 years, which is longer than I’ve been alive

What does your writing process look like in 2020, and how has it changed, as a result of COVID and the national uprising over police brutality?

My writing process is chaotic. Ha. I discuss it in an upcoming micro essay series in Poets & Writers.

The changes to my process during the pandemic have been overwhelmingly positive because of the community I’ve found in the Patrice Lumumba Writing Group and the Holla Back Poets Open Mic, which I’ve been going to on Tuesdays and Thursdays. This writing collective is out of the Bay Area, and I went once in-person while I was there, but when the quarantine came down, it went virtual and now we’ve been able to amass a coast-to-coast attendance that would’ve been impossible before. So, I’ve kind of built a routine around the writing group: gathering lines in my notebook over the weekend, composing live on a timer with the group in our Tuesday-night writing session, and then revising for the open mic on Thursday. The act of actually composing poems with other poets in real-time is a crucial activity that you don’t get in an MFA. In this group of poets, I have models, teachers, comrades, editors, and family. I can’t even imagine what this pandemic would be like without them. I’m closer to the writer I want to be now: closer to the people and the work.

Do you have words of hope for fellow Black poets and artists?

Well, first of all, I have a lot of faith in Black poets and artists to do what they already have in mind to do and say about our unfavorable conditions. Hope is a sort of passive emotion one experiences when one can’t influence an outcome. So, in that regard, most of my “hope” is directed at white people. As in, I hope they go look into when and why “white” entered the popular imagination as a word to describe a particular group of people, and why successive ethnic groups were gradually added to that larger group. I hope they learn their history. I hope they wake up one day and want to contribute all their efforts to a redistribution of the existing wealth and land among Black and Native peoples, which they have amassed via the brutality and murder of Black and Native peoples. I hope they come up with ways to divest from “whiteness” and its genocidal legacy not just for our sake, but for the sake of everyone’s continued existence on this earth. Things like that.

As a Black poet, I don’t necessarily think of myself as a hope manufacturer or hope worker. I think my role is as a reporter, a spiritual reporter, and keeper of the record, in the way Baldwin talked about the poet’s report in “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity.” When I hear “hope” in the kind of moment we’re in right now, as a clarion call to poets, I hear a collapsing of the necessary and painful struggle we are sacrificing in, I hear a hope that things will return to normal, which is a false peace. “Let me say peace to you, if you’re willing to fight for it!” said Fred Hampton.

If there is any hope in my mind for us, it is a revolutionary hope. Toni Cade Bambara said, “the role of the artist is to make revolution irresistible.” So, my hope is to write more and more poems, or to enter a conversation of poems, or for more poets to write poems that contribute to what the poet Tongo Eisen-Martin describes as “showing people that the system is not invincible or immortal” and “getting masses of people to find oppression unacceptable.”

NIGHTSTICK

In Kentucky you are a Black girl, but don’t know it. You sleep

next to it. Crooked bone, split-open head. Patrolling

through the night. Don’t even know you should be trying to run away.

It rests in your night terrors, in a bureau between your grandmother’s

quilts, with her thimbles & thread & dead white poems. Don’t think

for a moment your grandfather won’t pull it out, make a cross of it

with your arms, gift you its weight & crime. Do you believe?

What if he said its name was Justice? Would that be too much?

If he was the only man your childhood saw hauled away in handcuffs,

pale & liver-spotted & stiff in limbs sharp enough to fold into the back

of a cruiser? You. This bruise of irony. The only two Blacks ever allowed

in his house. & at night he be singing you to sleep while it sits invisible,

sentry-like out of sight. He be humming hymns—I come to the garden alone

while the dew is still on the roses—knowing how much blood it has seen

& whose. He be holding you to himself like a secret & every song be a prayer

for your daddy’s sunk-in head. You breathing one for his whole face

before you. Bullying a shit-shaded boy’s head is what it’s made for,

he say, your pappaw, while you hold it, not knowing enough about yourself

to understand the cannibal nature of chewing on his words with no riot

inside. No baton twirling in the air of your stomach. No notice of the grand

wizard & his wand when he appears in your nightmares. You be closed-eye

& it be there Black as who it means to beat

Horsepower will be on sale September 22 and is currently available for preorder. More information and work by Joy can be found at joypriest.com.

Horsepower author Joy Priest" title="Q&A with Horsepower author Joy Priest" class="news__image"/>

Horsepower author Joy Priest" title="Q&A with Horsepower author Joy Priest" class="news__image"/>

COMMENTS